1945 Fight Record

| Date | Opponent | Venue | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 02/05/1945 | Cal Rooney | Queensbury Club, Soho, London, UK | Won - TKO - Round 3 |

| 17/07/1945 | Jack London | White Hart Lane (Tottenham FC), Tottenham, UK - Commonwealth (British Empire) Heavy Title, BBBofC British Heavy Title | Won - KO - Round 6 |

| 24/08/1945 | Martin Thornton | Theatre Royal, Dublin, Eire | Won - TKO - Round 3 |

| 27/11/1945 | Jock porter | Royal Albert Hall, Kensington, London, UK | Won - TKO - Round 3 |

1945 - A BIG Year !

This was to be the big year - the British Heavyweight titles, both of them. Did Bruce know he would do it? From the focussed, determined path of his career so far, there doesn’t seem to have been any doubt. We are looking with hindsight, of course, knowing what happened; at the time, it must have felt very different. But Bruce was undoubtedly as tenacious as one of his own terrier dogs, and as purposeful as if he knew instinctively the trajectory of his future. If he could have seen it all, would he have been so resolute?

As preparation for the future, towards the end of 1944, Tom Hurst found an American manager to represent Bruce in the United States, the well-known Johnny Rogers, who managed Jackie Jurich, Lloyd Marshall, Manuel Ortiz, Gabriel Rios and Benjamin Gan, known as Small Montana, among others. And the American press were beginning to take an interest, with an American army reporter turning up at Mona Road and being astonished by the rustic training facilities at the Plough Inn.

1945 - Building a Challenge

Bruce also involved himself in entertaining the local troops with exhibition bouts at an R.A.F. camp, where he put on a show with A.B.A. runner-up John Streets and with his great hero and friend, ex-British and Empire feather-weight champion Nel Tarleton. Bruce had first met him in 1942, when Tarleton topped the bill on the night Bruce fought Tommy Moran. Tarleton had invite Bruce into his dressing room, to avoid the crowded single room given over to the supporting fighters, and proceeded to give Bruce a lesson in pre-bout composure and control as he lathered up and shaved himself meticulously with his cut-throat!

Tom Hurst had also laid the ground for what was to be Bruce’s biggest fighting success so far. He contacted Wilf Schofield, manager of Jack London, the current British title holder and negotiated a championship fight for July 17th. Significantly, the man handling the arrangements was Jack Solomons, who would become legendary among boxing promoters. Solomons was just starting up again after the limitations imposed by the war, and vowed that the Woodcock-London fight would go ahead at White Hart Lane ‘doodle-bugs or no doodle-bugs’ [Two Fists and a Fortune, p. 92]. In fact, not only did the fight go ahead but the war itself had finished in May. In that heady atmosphere of national and international celebration, the Woodcock-London fight was to become simultaneously the first great national success for Solomons and for Bruce, chiming with a national mood of success and aspiration. It was also the beginning of a profitable link-up for both men: Solomons would go on and promote a number of Bruce’s greatest fights.

2nd May, Woodcock vs Cal Rooney

But before that, there needed to be some build up. While London faced up to Ken Shaw, taking eight rounds to win on a technical knockout, Bruce took on Canadian cruiser-weight champion Cal Rooney. They met up at Soho’s Queensbury Club, functioning through the war as a boxing and jazz venue - Glenn Miller played there the previous year.

The fight with Rooney was short-lived. Bruce dominated from the start and in the third round, caught Rooney with a powerful right hook to the chin. He went down for a count of nine, only to get up and be felled by an equally strong punch. Despite staggering back to his feet, referee Teddy Waltham declared ‘That’s enough’ and announced Bruce the winner.

In the report, Jimmy Wilde, former flyweight world champion, wrote that Bruce’s ‘straight hitting from the shoulder was a pleasure to watch’, as was ‘his perfect timing with a right hook which has dynamic power’. He went on to say that ‘Woodcock is a calm, calculating boxer who studies every move essayed by an opponent. He is unquestionably the cleverest boxer among present-day cruiser and heavy-weights.’ [see archive once uploaded]

1945 - Build up to the Championship

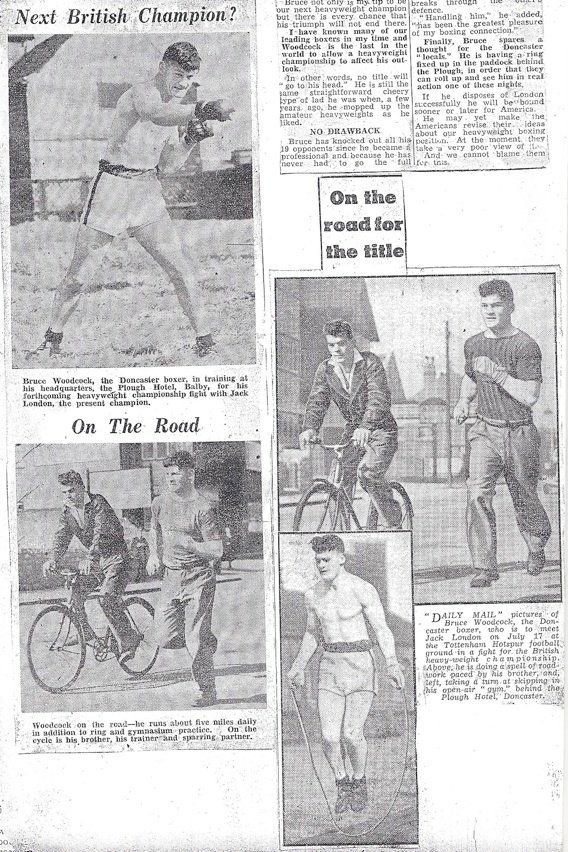

It seemed an easy build-up to the bid for the title, but behind it, and over the next two months, was a relentless regime of training and preparation, overseen as always by manager Tom Hurst and father Sam Woodcock. Bruce’s youngest brother, Billy, also joined in, accompanying him on his five mile road-work training, even if it was on a bike.

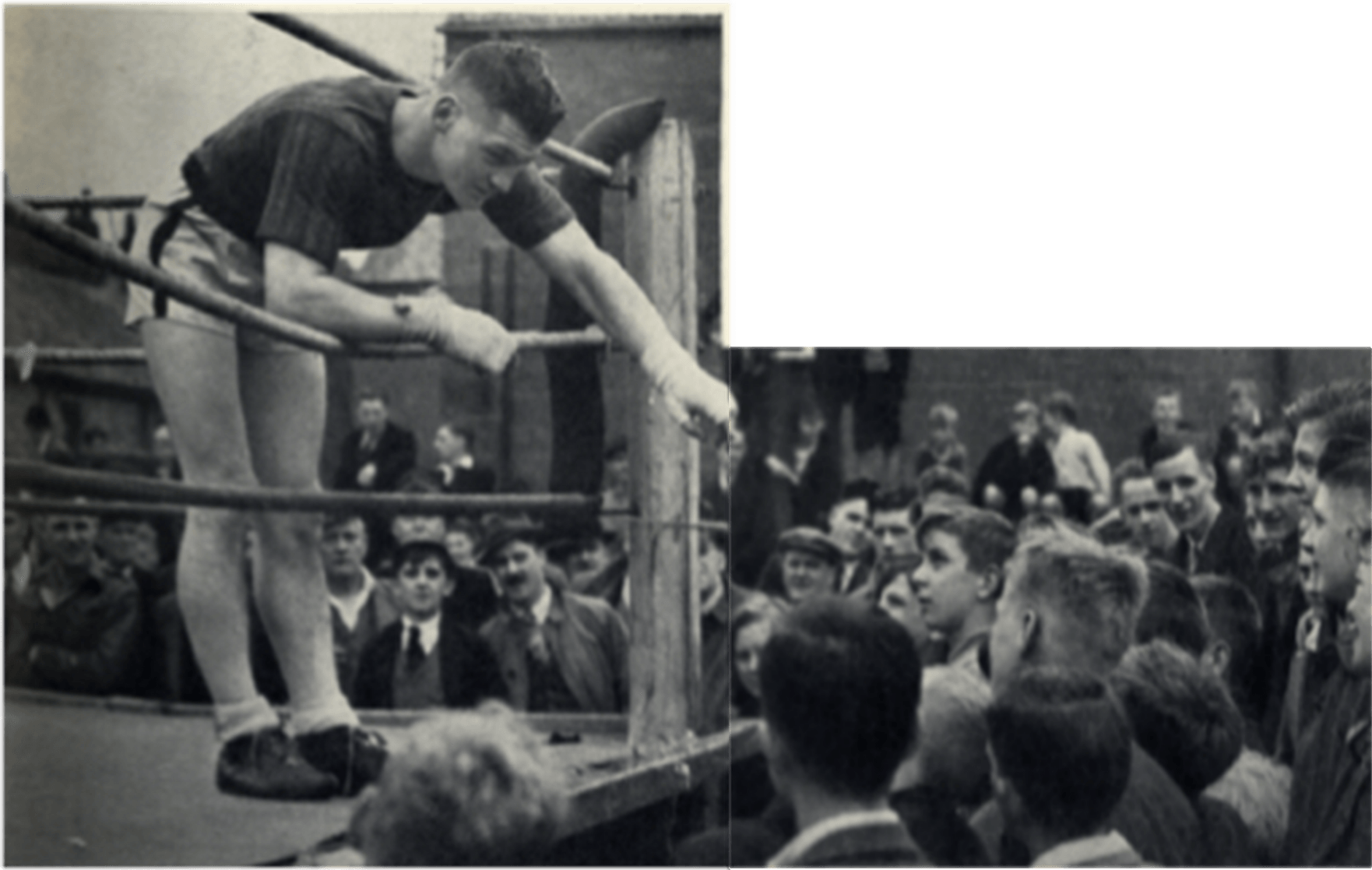

The training of course mainly took place at the Plough Inn, which had been taken over by a new manager, Edgar Smithhurst. He suggested that Bruce’s training team set up an outdoor ring in the small disused paddock next to his garden, an idea which appealed since the London fight was booked as an outdoor affair. The training team included a range of sparring partners, including Alf Brown, the Army heavy-weight champion at 14 st., Jim Saxton from Manchester at 16 and a half stone, and Bill Brennan from Durham who had fought London in the distant past of 1932, along with some local and regional amateurs. The sparring for a few rounds with each partner was watched by an appreciative audience of locals, particularly school-children who would crowd around the outdoor ring to cheer on their local hero.

17th July - A Date With Destiny

For the actual fight, local support was extensive and remarkable, considering the hard times of the end of the war: Solomons sold £5,000 of tickets in the Doncaster district; 500 of Bruce’s workmates had booked a day off to go down to see the fight; and the L.N.E.R. company gave Bruce a week’s holiday to complete his training. He was at the peak of fitness. Bruce’s weight at this point was 182 lbs, three pounds higher than for his fight with Marwick the previous August. And this was the weight at which he would face the 215 lb Jack London, with all his many years of experience since turning professional in 1934. This would be London’s 77th professional fight; it was Bruce’s 21st. But he would have the age advantage: he was 25 to London’s 32.

This was the first of Bruce’s fights to receive extensive coverage in the national press [see archive once uploaded] and it was also the first of Bruce’s fights to be filmed, as well as being broadcast by the BBC on their General Forces Programme [see Links section for an extract of the film and description of the broadcast]. The film footage gives some impression of the extraordinary scale and atmosphere of the fight: White Hart Lane was packed to the rafters with people. Estimates of the crowd vary from the Daily Mirror’s 38,000 to the Daily Mail’s 40,000. It was a huge gamble for Jack Solomons: the costs of the promotion, coupled with the deductions exacted by the Entertainment Tax, mean he had to lay out £20,000 before he would begin to show a profit. But with seat tickets selling at 10 and 5 guineas a time, the size of the crowd and the impact of the event more than justified his audacity, and it made Solomons’ career as the greatest European promoter of his time.

This was also the biggest event of Bruce’s life but if he felt daunted, there was no sign of it in his cool and determined presence, or in the courage and focus of his performance. As a talisman, Hilda, his mother, had made him a new pair of shorts in red and blue silk, stitched with his initials on the left leg, and with a ‘Good Luck’ note and a sprig of heather that Bruce had sent her when he’d gone camping on the moors as a youngster. Hilda made a point of not attending his fights: while she believed totally in Bruce’s ability, she couldn’t bear to see any of the punishment he might receive. And Bruce’s sweetheart, Nora Speight, later his wife, always felt the same. But his father Sam was there, as always, in his corner, as well as Bruce’s hero Nel Tarleton, and brothers Billy and Sam were watching. And as Bruce made his way to the ring, a huge swathe of Doncaster fans broke into a rendition of ‘On Ilkley Moor Bah t’at’, which was fast become Bruce’s signature tune. [see next section for an account of the fight]